3 COVID deaths leave Sparks family shellshocked, vulnerable and scared

Published 1:51 pm Tuesday, December 1, 2020

- Madeleine Sparks

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By Dwight Sparks

For the Enterprise

She had approved a draft of her obituary, selected hymns and Scripture for the funeral and doled out keepsakes to friends and family. In physical decline at age 95 and diagnosed with congestive heart failure, Madeleine Sparks figured she didn’t have long.

Then COVID-19 slipped inside her Farmington home. Her breathing became labored. She developed a cough and had no energy or appetite. In the Forsyth Medical Center emergency room, a nurse plunged a cotton swab deep into her nose. The results, “positive.”

“Isn’t that a fine howdy-do!” she said. “I guess this could take me out of here.”

Two painful, isolated, hacking weeks later, she became one of the 200,000 across America claimed by the scourge. The long-time Davie County High School chemistry teacher, mother of six, grandmother and great-grandmother died in a Hospice House in Dobson last week.

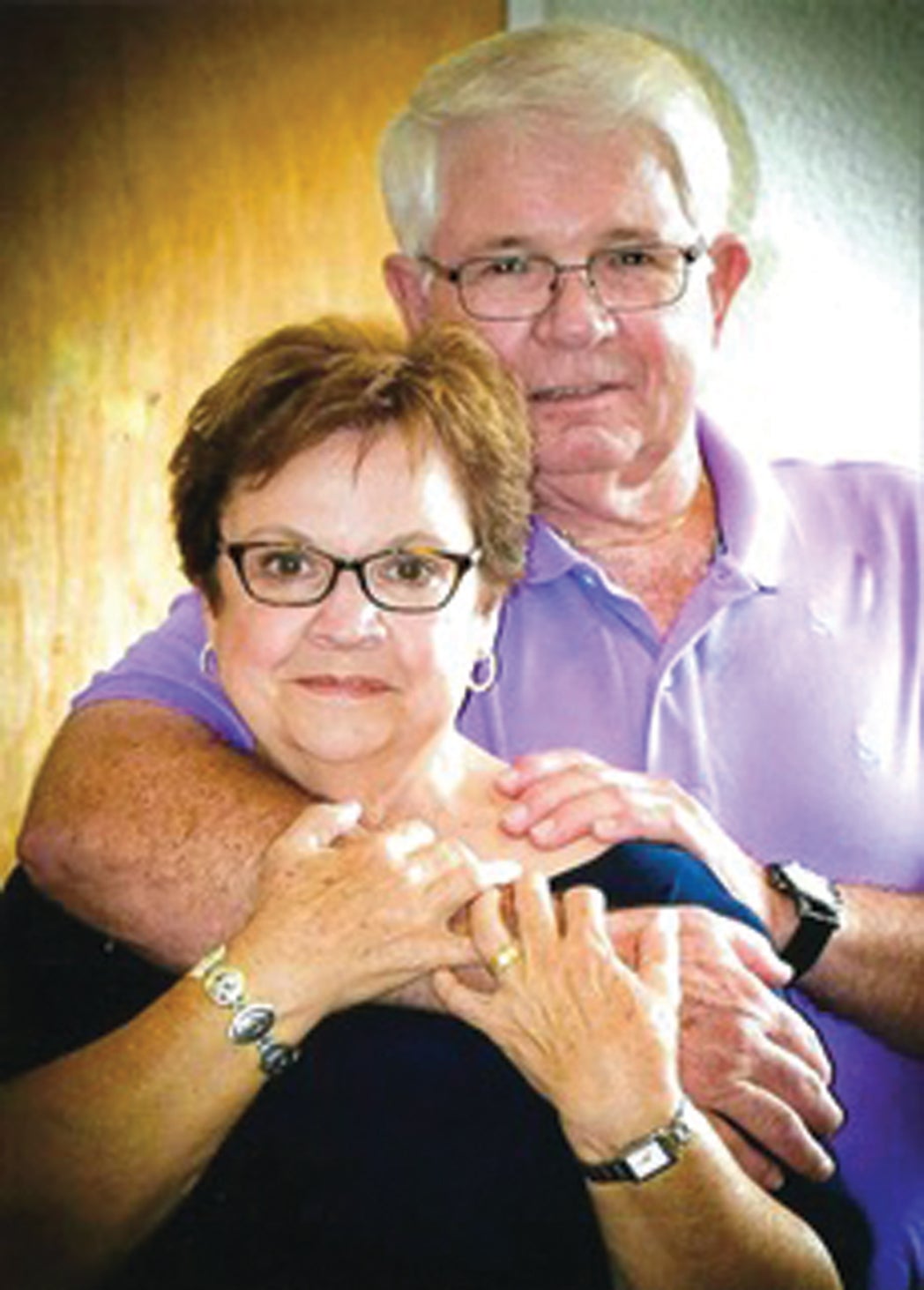

The close-knit family landscape altered tragically during her ordeal. A son and daughter-in-law, John Edwin and Carol W. Sparks, died of the virus three days apart. Two other children tested positive. Another was hospitalized. Daily, the virus attacked from a new direction, leaving us shellshocked, vulnerable and scared — our unsuspecting family a sudden hotspot of the invisible menace.

Every child who visited Mama that weekend was at risk — five of six. The sixth, ironically, hadn’t come for fear of bringing a grandchild’s bug.

I helped my invalid mother to bed the night before she was hospitalized. I watched her struggle to breathe. When the Davie County EMS unit and Farmington firefighters arrived to take her to the hospital the next morning, I jumped without hesitation to stay with my mother. The virus never crossed my mind.

In the ER, I helped answer the usual battery of nurse questions. The virus test was a precaution. The results were shocking. Hearing impaired, my mother didn’t understand the nurse. I had to loudly repeat the results.

“This is awful,” one sister texted.

Had I known the fates awaiting my brother and sister-in-law, I might have run from the room. Instead, I calculated this might be the last time I would see my mother. She would go into a lockdown ward at the hospital, no visitors, the chances of survival very slim. I stayed, taking solace in the national survival rates. Besides, I was already exposed.

We spent eight hours waiting for a bed to open on the virus floor. Mama retold all the familiar family stories and said nice things about me, skipping over the sleepless nights I caused her in my salad days.

“This is the day the Lord hath made. I will rejoice and be glad in it,” she quoted.

I struggled to choke out Psalm 121, one of her favorites since her college days at Appalachian. Too soon, the room upstairs opened. The staff wheeled her away.

“I’ll be all right,” she said.

She was nursed by a hospital staff costumed like space aliens, garbed in protective plastic from head to foot. After 13 days of seclusion, fright, coughing and hacking and sickness, she emerged drastically weakened, moving to Dobson. There, two of us children could be with her. Weakly and haltingly, she recited the 23rd Psalm for my sister and urged us to memorize it too. That would be her final testimony. She lost her voice the next day. A day later, she slipped into eternity.

Who can figure this virus?

It violently attacked my brother and sister-in-law’s lungs. Their oxygen levels dropped rapidly and couldn’t be restored. They were gone two and three days after going into the hospital. By contrast, my younger sister and I have had only minor symptoms. I only tested because my wife and children insisted.

From his deathbed, my brother pecked out a final text to us: “… it’s been wonderful being your brother and wearing the Sparks name.”

We siblings groaned in a chorus of typed despair.

We have been distraught and unable to grieve together for risk of more contamination. Two weeks later, the storm of infection has abated. I’ve got a couple more days of quarantine remaining. At night, I stay upstairs in the children’s old bedrooms. Elizabeth puts my meals on the stairs. By day, I blow leaves from the lawn as if nothing is wrong.

Physically, I’m fine. Emotionally, the family is a wreck. We buried my mother Saturday in a brief graveside service. I stood alone at a distance, not wanting to put anyone at risk. The promising new vaccine can’t come soon enough.