Black History: Davie natives successful

Published 9:53 am Thursday, February 16, 2017

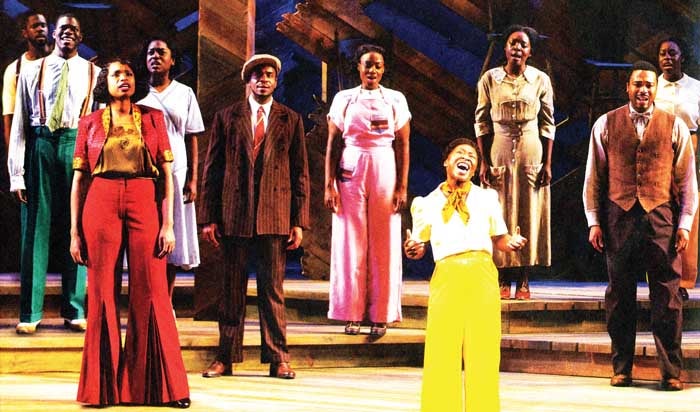

- Lawrence Clayton (Larry Brown) on Broadway in The Color Purple.

He’s known along the bright lights of Broadway as Lawrence Clayton.

Folks around here remember his as Larry Brown, the son of Jesse Brown III and Geraldine Tatum Brown of the Fork community.

The stage actor has been a success on Broadway, just finishing a more than a year stint in the musical, “The Color Purple,” at the Bernard B. Jacobs Theare on 242nd W. 45th St. Jacobs is one of the Schubert organization theaters.

Clayton played a double role: the preacher and Ol’ Mister. Both roles required a singing voice.

“Larry inherited an awesome singing voice from his Davie County Tatum and Brown families,” said Magalene Gaither. “Larry was outstanding in several musical numbers, ‘Mysterious Ways,’ ‘Somebody Gonna Love You,’ ‘Big Dog,’ ‘Brown Betty,’ ‘Shug Avery Coming to Town,’ ‘Uh Oh!’ and ‘The Color Purple’.”

The musical won two Tony Awards: Best Revival of A Musical and Best Actress to Cynthia Erivo, who played the role of Celie.

The production was Jennifer Hudson’s first Broadway appearance.

Clayton has also performed in the following shows on Broadway: “Bells Are Ringing,” “It Ain’t Nothing But The Blues,” “The Civil War,” “Once Upon A Mattress,” “The High Rollers Social and Pleasure Club” and “Dreamgirls.”

He was an award winner as Valjean in the 25th anniversary production of Les Miserables.

He is gearing now for one of the lead singing roles in the new musical concept of “Once on This Island.” This musical was composed by Lynn Ahrens and Stephen Flaherty, a story inspired from Hans Christian Anderson’s Little Mermaid. It is a fairy tale celebration of forbidden love, race relations, economic disparity, rite of passage and death, embellished with strong voices.

Rodney Ellis: Advocate for Public Education

Rodney Noel Ellis Sr. has rubbed elbows with past North Carolina governors as well as President Barack Obama.

His goal: to get support for public school teachers and students.

Ellis, a Davie native, died on Sept. 20, 2016. He was born in Mocksville on July 19, 1957 to Elizabeth Rivers and the late John William Ellis.

He was educated in Davie County Schools and in Cleveland, Ohio. He majored in education at Winston-Salem State University, where during his senior year, served as a student teacher at Lift Academy under the late Sen. Earlene Parmon, administrator. He graduated with honors in 1999.

He began his teaching career at Atkins Middle School, which later became Winston-Salem Preparatory Academy. His passion stood out among his peers, and he was voted teacher of the year twice during his first three years on the job.

He was a champion for teachers and students everywhere, advocating throughout his career. At WSSU, he was president of the student division of the N.C. Association of Educators (NCAE). He was elected Atkins representative for the Forsyth Association of Educators, and became president of that organization.

It led him to eight years in leadership roles at the NCAE, serving as vice president twice and president once. He served on state and national committees involving public education and frequently met with elected representatives, including President Barack Obama and former North Carolina governors. He received many honors from the NCAE.

He was a member of the Phi Beta Sigma fraternity, which bestowed many awards upon him, including the Delta Sigma Chapter President’s Officer Appreciation Award, Spirit of Sigma Award, the Centennial Legacy Award and the Man of the Year award in 2002.

He was a sportsman, and loved golf, basketball and stepping. He shared his passion for sports with young men in the community. He made sure that practicing in sports also included an educational component.

The local YMCA honored him with the Black Achiever Award in 2002.

His funeral was held on Saturday, Sept. 17, 2016 at St. Peters Church and World Outreach Center in Winston-Salem, with Pastor Gloria M. Samuels of Apostle Great Commission Community Church officiating.

Some of the remarks at his funeral:

Mark Jewell, NCAE president: “He committed his life to his family and to making public schools better for every child. We will miss his tremendous leadership at NCAE and his tenacious commitment to public education.”

Pat McCrory, governor: “Rodney was a dedicated advocate with a passion for public education. His devotion to North Carolina’s students was a labor of love.”

Beverly Emory, Winston-Salem Forsyth school superintendent; Rolanda Mays, president of the Forsyth NCAE chapter, also spoke.

Survivors include: his wife, Lisa Chisolm-Ellis; his mother, Elizabeth Rivers; children, Rodney Jr., Gabrielle, April, Alis and Rodney B.; sisters, Terza (Edward) Woody and Marcheta Ellis; brothers, Shawn (Amanda) Ellis and Bryant Rivers; mother-in-law, Ella Chisolm; sisters-in-law, Laverne Taylor, Theda (Jerry) Okono; aunts, Jimmie Nell Mayfield, Bernice Rousseau, Vivian Wright, Irma Rivers and Tressie Ellis; uncle, Russell Rivers; and neices, nephews and cousins.

Ellis himself had said: “There is a goal for NCAE, an objective, and that is to make sure that education for educators is the best experience it can possibly be; and in doing so, we benefit those children that we teach. It became my objective to restore the joy of this profession for both educators and students.”

His legacy was described by retired Davie educator Magalene Gaither. “The life and legacy of Rodney Noel Ellis Sr. is one of immense service. His unwavering commitment to students and educators will forever be imprinted in the DNA of public education. Rodney’s impact and influence will continue to go places that his feet never had the opportunity to touch. He was a man of many hats that left and irreplaceable mark on this earth.”

Cora Massey: Educator and Christian

Cora Lee Morton Massey moved to Mocksville on Sept. 27, 1944.

Her husband, the Rev. Robert Massey Sr., was named minister of Second Presbyterian Church on Pine Street. She taught English grammar and literature at the Davie County Training School.

She organized a drama club there, and produced several award-winning plays and dramatic exercises. She became senior class advisor and director of commencement activities.

At the end of the 1955-56 school term, her husband was asked to help organize and pastor a church for Negroes in Fayetteville. The church was built, and flourished, under the guidance of the Masseys.

Cora Lee Morton was born in Salisbury to the late Rev. James Mangum and Emma Laura Cundiff Morton on July, 17, 1917. She died on Jan. 18 of this year.

She attended schools in Rowan County, Barber-Scotia College, Johnson C. Smith University and the University of Pittsburgh.

In addition to teaching in Davie County, she taught at Cumberland County Schools, Fayetteville State Teachers College, and at Winston-Salem State University, where she retired as assistant professor of English and director of Student Teachers in English Education.

She was involved in church, civic, community and social organizations: Jack and Jill, Altrusa, and Alpha Art clubs. She was initiated in the first membership of Zeta Pi Omega Chapter of Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority in Fayetteville, and became a member of the Imicron Omega Chapter in High Point. She was recognized as a 50-year member (Golden Soror) of the sorority.

A Bible study leader, she was also an elder who was active in the United Presbyterian Women, Women of Church, COWAC and Church Women United.

She was a Presbyterial officer, the vice moderator and moderator of Yadkin Prsbytery, a commissioner to Synod and General Assembly, a member of the Committee on Ministry of the Salem Presbytery, trustee of Synod and Synod’s Judicial Commission.

She served two years as the Hunger-Action enabler for the Presbytery, and was a member of the Joint Hunger Committee for the synods of Piedmont North Carolina. She was on the national executive committee of UPW.

She was the first moderator of the Salem Presbytery’s women’s organization, and was a faithful church member wherever they lived.

The Masseys moved from Fayetteville and the College Heights Presbyterian Church they were instrumental in building, to High Point in 1970. Their son, Robert Massey Jr., remains at College Heights, where the R.A. Massey Sr. Educational Building is still in use.

Her survivors include: children, Barbara Lee (Richard Kimmel) of South Carolina, Wilbur (Shirley) of High Point, Robert Jr. (Joyce) of Fayetteville, and Avys, of the home; grandchildren, STacy Monique of Greensboro, Robert Aaron III of Fayetteville, Christopher Alexander of the home, Courtney Massey of Charlotte, Robert A Massey IV of Laurel, Md.; and many nieces, nephews, other relatives and friends.

Her nine siblings and her husband preceded her in death.

Karen Parker: A Trailblazer

Karen Lynn Parker is a woman to remember.

Born on Sept. 22, 1944 to Fred D. and Clarice Holt Parker (now deceased), her parents moved from Salisbury to Davie County to teach. Of course, they brought along Karen Lynn, 3.

Her father taught chemistry at Davie County Training School and her mother taught in the Mount Zion School #1 in Advance. She was tended by Golden and Rachel Frost Neely on Pine Street in Mocksville.

Later, the Parkers moved to Winston-Salem for new teaching positions.

Karen Lynn Parker completed high school and attended Greensboro Woman’s College for two years before transferring to UNC-Chapel Hill to study journalism, where she graduated in 1965. The move was a requirement at the time, and her experiences at UNC mark her as a woman to remember.

In November, 2016, UNC celebrated its 223rd birthday with an initiative to name grants and fellowships to honor 21 people who represent firsts in university history.

Karen Lynn Parker, class of 1965, was the first black person to attend the campus as an undergraduate student.

She described in a 1999 interview on UNC-TV how she was unaware at the time that she was blazing this trail.

“I kind of discovered this when they put me in a dorm on the fourth floor, very top, in a room by myself, and there was this empty bed, and I kept waiting for someone else to show up and nobody did.”

Later, her friend who lived in another wing of the dormitory, decided to move into her room. Their parents were called in to approve of the new living arrangement.

She chronicled her years as a student, including descriptions of her experiences during the Civil Rights Movement, in a diary which she donated to Wilson’s Library Southern Historical Collection in 2006.

The first entry, dated Nov. 5, 1963, begins with her reflections on the freedom marchers. Her next entry, Nov. 22, related her shock and sadness at the assassination of President Kennedy. She wrote that classes were called off, tests were cancelled, and the Duke-Carolina game and the Beat the Jock parade were struck from the calendar. She wrote that she felt “insecure, unsafe,” and that “the future looks uncertain.”

However, she took hold of the present. As part of her activism with the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), she often spent time in jail. In her diary Dec. 18, she wrote: “On Saturday the 14th, I decided to go to jail. Leo’s was a restaurant Downtown Chapel Hill with a policy of segregation.”

As time wore on, she continued to demonstrate against segregation with other students and members of CORE, which had been accused of communist leanings, and the university had threatened student demonstrations with expulsion.

She said she felt her faith in Carolina waver.

She was summonsed before the Women’s Human Council in 1964. She remained firm: “They are going to have to expel me because I’m not going to give up.”

The university now will award as many as 25 Karen L. Parker grants to undergraduate students next year.

Although she was the only black woman in her class, five black men also graduated in 1965. They became a heart surgeon, a rear admiral in Navy intelligence, a researcher at Brookhaven National Laboratory, a biology professor and a certified public accountant.

She enjoyed a successful career in journalism with the Grand Rapids Press (Michigan), the Los Angeles Times and the Winston-Salem Journal. She is a past member of the UNC General Alumni Association Board of Directors.

She said: “Looking back, I really felt that I should have done more, but really there was not much more I could have done. All the brash things I did were things I felt needed to be done. I had to be a role model for those who came behind me.”