Buck Jordan most successful Davie Major Leaguer

Published 9:41 am Thursday, July 28, 2016

- Baxter Jordan is the only player known to have pinch hit for Babe Ruth.

When Whit Merrifield was called up to the Kansas City Royals on May 18, he became the fifth major leaguer from Davie County – and the first in 71 years.

A Davie County native had not played in the big leagues since 1945.

• The first major leaguer from Davie was Fred Anderson of Calahaln. The pitcher debuted in September 1909 and played in the majors for seven years, his career ending in July 1918. He played for the Boston Red Sox in 1909 and 1913. He played for the Buffalo Buffeds in 1914-15 and the New York Giants from 1916-18. He had a career record of 53-57 with a 2.86 ERA in 178 games, including 114 starts. His best year: 19-13 record in 1915 for Buffalo, including 14 complete games and five shutouts. Anderson died Nov. 8, 1957 in Winston-Salem at the age of 71.

• Thomas Edward Seats of Farmington was a lefty pitcher for the Detroit Tigers in 1940 and the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1945, his career interrupted by World War II. In his rookie season in ‘40, he went 2-2 with a save and a 4.69 ERA in 55 2/3 innings. He made two starts and 24 relief appearances. In ‘45 for the Dodgers, he went 10-7 with a 4.36 ERA in 121 2/3 innings, making 18 starts and 13 appearances out of the bullpen. Seats died May 10, 1992 in San Ramon, Ca., at age 81.

• Zebulon Vance Eaton (“Zeb”) of Cooleemee was a pitcher and pinch hitter for the Detroit Tigers, debuting in April 1944 and playing his last game in September 1945. His two-year career saw him go 4-2 with a 4.43 ERA in 69 innings. He had a .214 batting average, with nine hits in 42 at-bats. Eaton died Dec. 17, 1989 in West Palm Beach, Fl., at age 69.

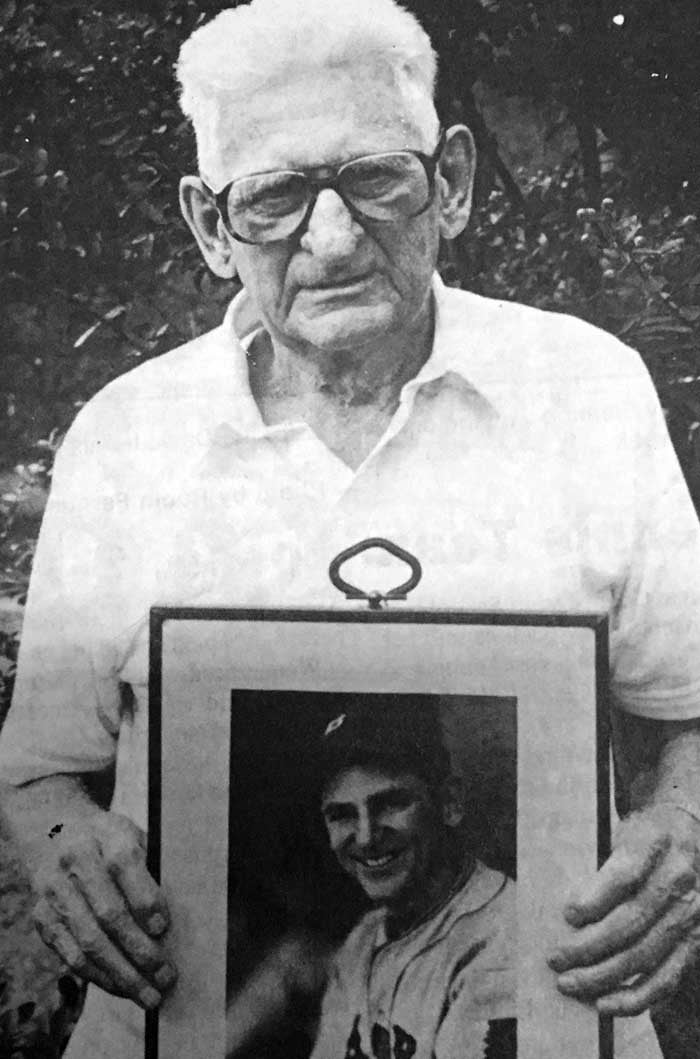

Baxter “Buck” Jordan

There’s no question who the most successful major leaguer from Davie County is. Baxter Byerly Jordan of Cooleemee, who was nicknamed “Buck,” put together a superb 10-year career from September 1927 through October 1938 while playing for the New York Giants, Washington Senators, Boston Braves, Cincinnati Reds and Philadelphia Phillies. He died March 18, 1993 in Salisbury at age 86.

The first baseman/third baseman was a .299 career hitter, with 890 hits in 2,980 at-bats. He only struck out 109 times. He spent the bulk of his career with Boston, playing six years for the Red Sox from 1932-37. His career average with Boston was .301.

But wait. It gets better. Jordan’s photo was on the Wheaties cereal box in 1936. He played one season with Babe Ruth. He was the only man to ever pinch hit for Ruth. And he was once interviewed by a young sportscaster named Ronald Reagan.

In September 1989, Jordan, at age 82, was interviewed by the Enterprise from his home in Salisbury. He looked back at his childhood, growing up in Cooleemee and working at the cotton mill.

“I was working 20 looms at the age of 16,” Jordan said in 1989. “I didn’t want that the rest of my life. Cooleemee had to be one of the best baseball cities in the state then. I played on the community team as a teenager in a league with Faith, Salisbury and Granite Quarry. I knew then I wanted to make baseball a career.”

At age 20, Jordan was playing for Charlotte in the South Atlantic League. John McGraw, manager of the New York Giants, came to watch Jordan and then bought him and two other Charlotte players for $7,500.

“Guess how I found out about that?” Jordan said. “We were playing in Knoxville. I got the morning paper, went to the bathroom and read it in there.”

Before reaching the majors, Jordan played in the New York-Penn and International leagues. For the Newark Bears in 1930, the 6-0, 170-pounder hit a team-best .352 in 136 games.

“I played for Newark in 1930 and 1931 and Sports Illustrated said we were as good as any team ever,” he said. “There wasn’t that much difference then from the International League and the major leagues. One player from West Virginia told me every time he got a hit, it meant one more day away from the coal mines. It was the same way with me. I didn’t want to go back to that mill.”

After the right-handed throwing and left-handed hitting first baseman hit .336 for Newark in 1931, the Washington Senators drafted him. He was traded to Baltimore and then to the Boston Braves.

Jordan did not disappoint, hitting .321 in 1932 as a Boston rookie. And boy did he keep it going. In 1933, he hit .286 in 152 games. In 1934, he hit .311 in 124 games. In 1935, he hit .279 in 130 games. In 1936, he hit .323 in 138 games. In 1937, he hit .281 in 106 games between Boston and Cincinnati. In 1938, his final year, he hit .300 in 96 games for Cincinnati and Philadelphia.

Impressive stuff, especially when you consider he played six years in “the toughest ballpark in the majors (in Boston),” he said. “The wind always blew in from right field off the Charles River, and I saw one lefthander hit a home run there in all my years.”

In 152 games for Boston in 1933, Jordan struck out just 22 times. His crowning moment came in 1936, when he hit .323 with 66 RBIs and made the cover of Wheaties. That year he was the first National League player to reach 100 hits. He led the team in average, was second in hits (179) and doubles (27), was third in runs (81) and fourth in RBIs.

“That would be like hitting .360 in St. Louis or the Polo Grounds,” he said. “Nobody hit at Braves Field.”

The first athlete to appear on the Wheaties box was Lou Gehrig in 1934. Michael Jordan appeared on the box 18 times, but he wasn’t the first Jordan.

“I got $100 for letting them put me on there,” he said. “How much does Michael Jordan get? Whenever I hit a home run, they gave me a case of Wheaties. There were 24 boxes to a case, so if nothing else, we always had Wheaties to eat.”

Jordan was among the first players to hold out for more money.

“After my 1936 season, I was making $8,000, which was good, but I wanted more,” he said. “So I told Boston I wanted $12,000. With the money floating around today, that doesn’t sound like much, but it was then. They told me I was already making top dollar, but I didn’t think it was enough. … I bought a farm (in Salisbury) with plenty to spare. Shoot, if you had $10,000 back then, you could have bought all of Rowan County.”

Jordan was not afraid to speak his mind. He refused to play night games. “I played on fields with three lights,” he said. “You couldn’t see the ball until it was right up on you. I hated it.”

He came along way before artificial turf. “I despise the stuff,” he said. “But I could have added 40 points to my average. A lot of my grounders would have gotten through.”

How cool was it to spend one season on the same field with Babe Ruth? Ruth was 40 and washed up in 1935, but it was still an unbelievable feeling to be teammates with the Bambino. When Jordan became the only man to pinch hit for Ruth, “it was just an exhibition, but it still meant something,” he said.

After hitting 659 of his 714 home runs for the New York Yankees from 1920-34, Ruth returned to Boston, where his career started in 1914. He didn’t have much left, hitting .181 in 28 games, including his final six homers. It was a rough season all the way around as Boston went 38-115. Boston had won 77, 83 and 78 games in Jordan’s first three years there.

“He was the greatest thing that ever happened to baseball,” Jordan said. “I don’t care how good you were, you were always in awe of Babe. And here I was, a guy from Cooleemee, North Carolina, on the same team. It was really something being with him.

“When Babe came to Boston, he was an old man then. When he played, his knees were taped and he had aches and pains. But the Braves wanted him badly. They made him vice-president and gave him practically everything he wanted. But it worked. The fans came. Our best day was always Sunday when over 40,000 would show up at Braves Field. They were all there to see The Babe.

“(One game) the stands were packed and everybody there came to see Babe. He wasn’t starting that day and somebody told him all those kids came to see him play.”

Late in the game, Ruth stepped in as a pinch hitter. He struck out.

“When he walked back to the dugout, he had to tip his cap to the crowd,” Jordan said. “They were giving him a standing ovation.”

Jordan’s major league career was over, at age 31, following the 1938 season, even though he hit .300 in 96 games between Cincinnati and Philadelphia.

It was an amazing 10-year ride. One conversation with Ruth meant everything to Jordan.

“I used to come to the park early for batting practice,” he said. “One day Babe watched me hit a few and came over. He said: ‘If I could swing the bat like you, I’d hit .500.’ He was the greatest person baseball has ever seen.”

In 1938, Jordan returned to Salisbury and moved in the same house that wife Mildred grew up in. He began a career in farming. Baxter and Mildred celebrated their 64th wedding anniversary in 1989. Both were battling cancer at that time.

“I had never been anywhere before baseball,” he said. “I guess the farthest I’d been was Salisbury. When I played in Charlotte, I took the train through Mooresville. So Boston was different. We lived there during the season and rented an apartment in Salisbury during the offseason. I’m positive I played with the best the game has ever seen. I was lucky.”