To hell and back: Harold Frank’s story

Published 9:38 am Thursday, May 7, 2015

- Harold Frank talks about his time in a German prisoner of war camp.

Harold Frank marched off the ship into chest deep water, carrying a rifle, grenades, rations – so much equipment that if he had fallen, he couldn’t have gotten up.

But he didn’t fall. He kept marching.

It wouldn’t be long before he marched into the gates of hell, a bullet in his shoulder and a will to survive. And after a year in a German prisoner-of-war camp, on May 7, 1945, he marched out – 100 pounds lighter on his already lean body – but he marched out.

What he had seen and endured still brings tears to the eyes of the tough man. His voice still quivers.

It surely wasn’t the 20th birthday he had expected growing up in the rural Tyro community of Davidson County.

The son of Edward Lee and Annie Wood Frank, born at home on Sept. 30, 1924, he was the second of five children. They rented crop land to grow cotton and sweet potatoes. They were poor, but never went hungry. His parents were loving, but strict.

Frank had a good crop of sweet potatoes his senior year of high school, and used the money to pay for his dilpoma, cap and gown. It was 1942, and World War II was in full swing.

He had also grown to be good with a gun. Frank remembers well a neighbor, Joe Sink, paying him a nickel for every blue jay he killed from his pecan trees. That was fun and easy work for a young Harold Frank.

He rode his bicycle to the Little Yadkin Finishing Co. to ask for a job. He got the job, and daily rode to a bus stop in Tyro that carried workers to the plant. Life was still hard. When he came home at night from work, he would feed his younger brother and change his diaper, giving his mother a break from the never-ending chores.

“They made us walk the line. Thank God for that,” he said of his parents.

Uncle Sam Calls

In May of 1943, Frank was drafted. He had never left his close-knit community, but boarded a bus headed for Camp Cross, S.C. He learned his first lesson on that bus, when an older recruit tricked him on a card game, but wouldn’t take his money. “He said, ‘I know you ain’t never been nowhere.’ It taught me not to fall for tricks.”

That $10 the other recruit returned to Frank was all he had.

The recruits were divided into branches of service, and Frank, on his father’s advice, chose not to join the Marines, they were the first to go to battles. He wasn’t a good swimmer, so the Navy was out.

He chose the Army. “They made it sound good,” he said.

At age 18, he got a two-week pass to go home. He stood up on a bus from South Carolina to Lexington. Train and bus trips continued to various posts. Frank remembers making $50 a month. He sent $18 home to his mother. “Momma and daddy was having it hard. She needed it more than I did. I tried to write to her every week, and I told her to spend it.”

She never did. When he finally made it home, the money was in the bank – in his name. “That’s the kind of momma I had,” he said.

It didn’t take long for Frank to excel with guns in the Army. He was assigned the Browning BAR, an automatic rifle that could fire 400 rounds in a minute. He got the highest score shooting the BAR, and he could take it apart and put it back together while blindfolded.

He was proud, but had no idea what that skill would mean for his future. “It was a good weapon, but I didn’t know what I was getting into. We ate and lived Army. I was trying to make a good soldier.”

He hopped on a train from Mississippi while on a 15-day furlough, riding to Lexington on the 24-hour trip. He had 15 cents in his pocket, and enjoyed the visit.

It was back to the Army. He had qualified for officer training, but turned it down. “I wanted to get over there and kill some Japs and Germans,” he said.

Eventually, he was sent to Ft. Meade, Md. “I knew they were up to something.” En route, he almost jumped the train and headed home when it was stopped in Raleigh because of a wreck. “The MPs caught us and threw us back through the window.”

Frank was now being trained with gas masks, and he volunteered to be qualified with the M1 rifle. “I liked to shoot. That’s all there was to it. I know’d we were going overseas.”

He had never used a telephone, and his parents didn’t even have one, but Frank managed to call his sister in Lexington to tell the family he was being sent overseas.

His parents immediately left for Maryland. Frank was called in to see an officer early the next morning. He thought he was in trouble, but it was his parents. The Army allowed him the day off, and they toured Washington, D.C.

“I kissed them good-bye and told them I would see them later.”

Across The Ocean

In March of 1944, Frank was on his first ship, headed across the Northern Atlantic to Scotland. “I got sick before we ever lost sight of land. I was sick all the way across. We got there and I got down and kissed the ground.”

He was sent by train to England, and from there across the English channel to France as part of the D-Day Invasion. It was then he realized that the Army knew all along what was in store for the sharpshooter from Tyro.

He had injured his knee and it hurt, but Frank marched on from Utah Beach. There were no decisions to be made now, it was survival.

He and another soldier dug a foxhole, and took turns on two-hour shifts. They thought they had done a good job with their three-foot deep foxhole until the shells started hitting nearby. They went back to digging, and it was chest high when they were finished.

His mate was burned by a piece of shrapnel, but they endured the hot days and cold nights. The invasion, however, had stalled. They sent a patrol to go behind the German lines, to find out the reason for the delay.

Frank was part of that patrol.

He remembers firing 60 rounds into a German “machine gun nest,” not knowing if he hit anyone or not. He slid down a dirt embankment, landing on a German. He stabbed him with his knife, but he was already dead.

The Real Hell Begins

By the time Frank reached a road, his group was being pelted with machine gun fire.

“I’m not sure what happened. I made it across the highway and stayed there all day on July 7. We dodged them and shot at them.”

Frank had been shot in the shoulder. The bullet was still inside him. At first, he thought a horse had kicked him. He knew he couldn’t raise the arm higher than his shoulder.

The Germans had flooded a ravine, or hollow as Frank called it. He gave away his BAR because he couldn’t carry it with the injury, and began swimming.

“I don’t know how I got across, but when we walked out, there was this German guy there with a machine gun. He had us.”

They were ordered to march with their hands above their heads. Frank was allowed to put his on his head. Those who couldn’t march were killed and thrown onto the side of the road.

They marched for a day, with no food or water.

The next day, he was interrogated by a German officer, who had noticed his German-sounding last name. “He said, ‘Frank, you’re fighting against your own ancestors.’ I said no, my ancestors are from Tyro, North Carolina.”

For some reason, Frank had carried his grandfather’s pocket watch, a family heirloom he had inherited. When that German officer demanded it, Frank let it fall to the floor while handing it over. The German officer kicked the broken watch, but allowed Frank to pick it up and put it into his pocket.

Still, the prisoners weren’t allowed to sleep. The walked all night with their hands up. They marched at night and hid during the day, across France into Germany to Stalag IVB, a prisoner-of-war camp. Food was bad and scarce and the water was worse. “Every morning, they would come in and pick up the dead ones,” Frank said.

The bullet in his shoulder had caused an infection. There was another American prisoner who was a medic, and he helped. “I know’d my time was limited,” Frank said. “That guy started doctoring on me and he healed that place up. He saved my life, ain’t no doubt about it.”

To this day, Frank has no idea what happened to that medic.

He had made a friend, another prisoner from the South. “I told him we’ve got to get out or we’re going to die in here.”

The next day, guards sought volunteers for a work detail. They volunteered. “We didn’t think it could get no worse,” Frank said.

They were transferred to barracks at a paper mill, where they worked 12 hours a day seven days a week. He was losing weight constantly.

Because that lodged bullet limited his ability to work, the Germans sent him to have it removed. It was lodged under his shoulder blade.

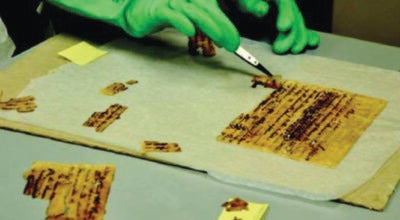

“That doctor cut it open. I felt it, but it didn’t hurt. Then he went in with the pliers. By God, I felt it then.” It had been three months, eight days since he had been shot. It was Friday, Oct. 13, 1944 and the doctor took the bullet out and plunked it in a dish. Frank, who had been learning to speak a little German all along, asked if he could have the bullet. The doctor gave it up.

Frank wears that bullet around his neck every day, along with his Army dog tags, Bronze Star and Purple Heart.

That doctor was one of the “older” Germans, Frank said. They were decent. A foreman at the mill had seen Frank’s broken pocket watch, the one inherited from his grandfather. He took it. A few days later, the guard returned with the watch, with a repaired glass crystal.

Frank still has that pocket watch.

The young guards, Hitler Youth, were “mean bastards,” as Frank calls them. The youth were allowed to throw rocks at the prisoners – for fun.

“They would tell us what to do … and if we didn’t do it, they would knock the hell out of you.”

There was never enough to eat, but Frank had noticed big rabbits – really big rabbits – scampering among the logs at the paper mill.

He took a rubber tube, and a branch from the scrub tree at the prisoner’s barracks and made a sling shot. A guard had given him some pieces of metal. He killed some rabbits when he could get by with it, and at night, he and a few other prisoners would boil them in water, eat the meat then drink the water.

At times, they could hear the bombs landing. The Americans had a superior Air Force, Frank said, and were bombing all around. A guard got Frank and a couple of prisoners some paint, and at night, they went on top of the barracks and painted “POW” in large letters. That guard may have saved their lives.

The bombs were really coming down on Saturday night, April 11, 1945. When it was over, every building was on fire except the prisoner barracks. The pilots could see the barbed wire enclosure and the “POW” painted on top.

They were told that night they were moving, because the Russians were coming. Prisoners, civilians, everyone was crammed onto the roads that night, Frank said. They marched all day Sunday and Monday. They had no food or water or sleep until Tuesday morning.

When they left, there were 107 prisoners. Now, there were 70 left.

He and his friend escaped, hiding in barns in the day moving at night, stealing potatoes from fields. They tried going into a small town, but there was a road block. Their POW uniforms were a give-away. Luckily, the guard was one of the older guys. “I convinced him, talking in German, to let us through.”

They made it about 30 yards when another German officer commanded “Halt.” They talked to him in German, too, but speaking in English, talked junk about him. That German knew English, and returned Frank and his buddy to the prisoner-of-war group. They had been gone for almost a week.

On May 7, 1945, they were marching somewhere “out in the country” and they stopped. The guards started changing into civilian clothes. “They told us the war was over. We were free to go.”

Free Again

Go where?

“We just sat there. We talked about it,” Frank said.

They started walking. Not marching. Just walking.

They had a little German money, and came into a village. The smell from the bakery was intoxicating.

“We bought every loaf of bread they had. We went down the road eating our loaves of bread.”

Telling this story, Frank’s smile comes back to his face.

It wasn’t long before they were found by fellow Americans, who took them to a kitchen. “They let us eat everything we could eat. We all almost died from over-eating.”

There were a couple of more skirmishes before they were airlifted to Camp Lucky Strike in France. Again, for a country boy from Tyro, it was a first. His first airplane flight – and there were no doors.

They met Dwight Eisenhower, had a meal with him. Eisenhower procured a telephone so that each of the former prisoners could call home. His parents had been told he was missing in action, then five months after he was captured, that he was a prisoner of war.

One would think the danger was over. But on the crowded ship on the way home, there was almost a collision with a huge floating mine bomb.

Home At Last

Frank made his way back home to Tyro. A stay in an Army hospital in Tennessee helped him to recover emotionally and physically.

The scars do remain. “I wonder why I survived and so many didn’t. That’s what tears me up. Over 400,000 lost, most in their early 20s, most just …”

And here, Harold Frank from Tyro, not far from a boy shooting at jay birds – had turned 20 in a prisoner of war camp.

“I never thought I’d live to be 21. Somebody was looking after me and it has to the the Lord. But think what those 400,000 could have done for this country.”

He met and married the former Reba McDaniel, and they raised a family in the Cornatzer community. He had a career at RJ Reynolds, and as a reserve deputy with the Davie County Sheriff’s Department. He helped found the Cornatzer-Dulin Volunteer Fire Department.

His wife is a resident at Davie Place, but even at age 90, he still visits her about every day. He cared for her at home until last winter, when his loss of hearing made it difficult to hear her when she needed help.

He still lives at home, with a son. He still raises fighting chickens, but gave up that hobby when it became a felony.

A nephew calls him a hero.

Frank disagrees.

“I ain’t no damn hero, but he thinks I am.”

So do a lot of other people.